Oral Lichen Planus and Oral Lichenoid Lesions

Oral lichen planus (OLP) and oral lichenoid lesions (OLLs) include a group of oral mucosal disorders that likely represent a pattern of common reactions in response to extrinsic antigens, altered autoantigens and superantigens.

Historically, there have been debates and controversies, which are still unresolved, regarding the terminology for OLP and OLLs, and we still lack definitive clinical diagnostic and histological criteria to differentiate OLP from OLLs. There is also no consensus on the possible clinical and behavioural differences regarding the risk of malignant transformation between OLP and OLLs.

OLP was included as a potentially malignant disorder in the 2005 classification and was recently confirmed in the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Oral Cancer Workshop held in the United Kingdom in 2020.

Oral Lichen Planus

OLP has been defined as “a chronic inflammatory disorder of unknown etiology with characteristic relapses and remissions, displaying white reticular lesions, accompanied or not by atrophic, erosive and ulcerative and / or plaque-type areas.” Lesions are frequently bilaterally symmetrical. Desquamative gingivitis may be a feature.

Prevalence:

- Estimated prevalence of 1–3% of the population. OLP is the most common mucocutaneous disease of the oral cavity.

- Preference for the female sex

- Increased risk of development after 40 years of age, with a mean age of presentation of 50–55 years .

Malignant Transformation:

In an analysis that exclusively included those publications that met strict quality criteria, the authors observed a malignant transformation rate of 2.28% for OLP.

Risk Factors:

- lingual location

- the presence of atrophic/erosive lesions

- tobacco and alcohol consumption

- human papillomavirus

- hepatitis C virus (HCV)

- presence of aneuploidy

The maximum risk of developing oral cancer is between 3 and 6 years after first diagnosis of OLP.

Patients with OLP and OLLs can develop multiple malignant lesions, which do not always develop at the site of pre-existing lesions. The OSCC that develops in patients with OLP and OLLs shows favorable prognostic parameters, especially in terms of mortality rate.

Clinical Presentation:

The distinctive clinical characteristics of OLP are represented by the presence of white papules that enlarge and fuse to form a reticular, annular or plaque-like pattern, so-called Wickham striae.

- 6 clinical subtypes of OLP have classically been described, which can be observed individually or in combination: reticular, plaque-like, atrophic, erosive/ulcerative, papular and bullous. We discuss 2 subtypes (keratotic/white and erythematous/red).

- Usually present with lesions of more than one subtype simultaneously

- Most commonly affected locations are the buccal mucosa, the lateral and dorsum of tongue and the gingiva

- Almost always a bilateral distribution, which is more or less symmetrical

- Course of OLP is characterized by relapses and remission, with intervals of several weeks or months, both of the clinical signs and symptoms.

Keratotic/White Oral Lichen Planus:

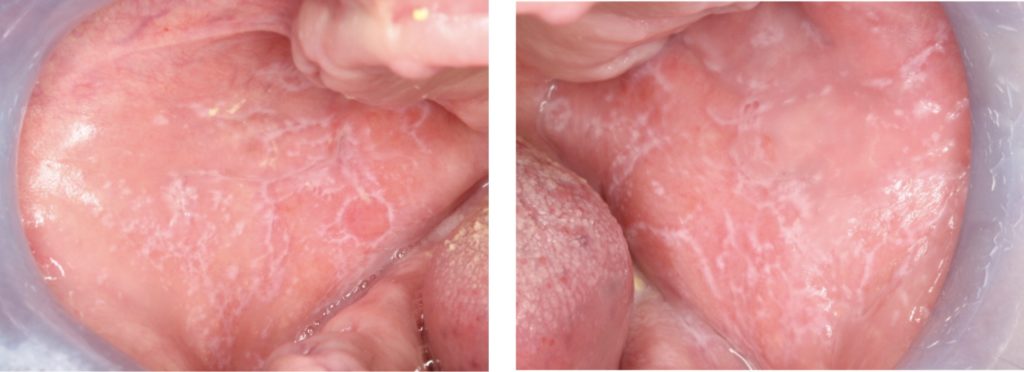

- Most recognized form of OLP, characterized by symmetrical white reticular lesions (Wickham striae) and less frequently as white papules or plaques (Fig. 1).

- The plaque form of OLP appears as a homogeneous, slightly elevated, multifocal white plaque, which typically affects the tongue and buccal mucosa (Fig. 2c).

- Generally asymptomatic – usually an incidental finding during routine examination of the oral cavity by dental practitioners.

Erythematous/Red Oral Lichen Planus:

- Can present as an area of atrophic mucosa or as red lesions due to hyperemia of the oral mucosa.

- Areas of erythema can be accompanied by ulceration and are often associated with white keratotic striae (Fig. 4).

- Variety of symptoms, from a mild burning sensation to debilitating pain. Lesions may interfere with speech, chewing and swallowing.

Desquamative Gingivitis:

- Erosive lichen planus located on the gums presents as desquamative gingivitis (Fig. 6).

- OLP is the most common cause of desquamative gingivitis, followed by pemphigoid and pemphigus (23).

- Buccal gingiva is most commonly affected.

Extra-oral Manifestations:

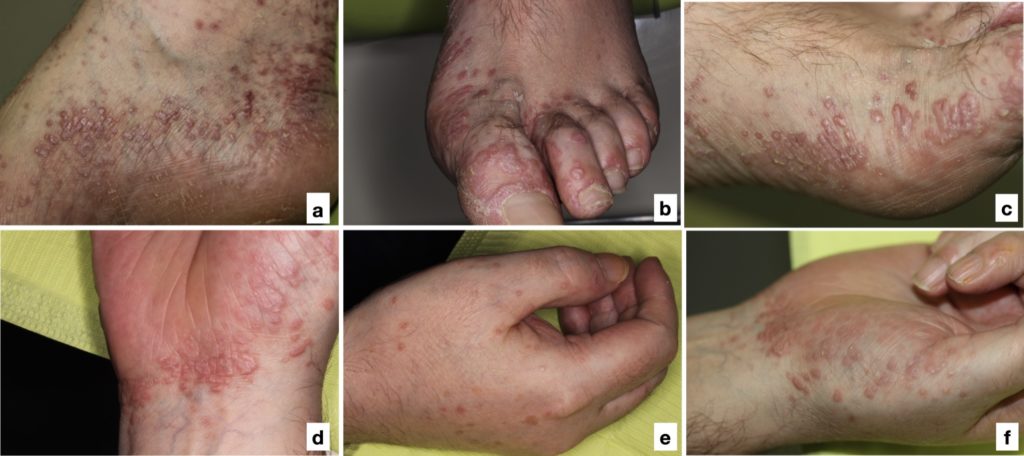

- 15% of patients with OLP develop cutaneous lichen planus, up to 60% of patients with cutaneous lichen planus have oral manifestations

- Presents as a papulosquamous rash with purplish, flat-topped bumps, of varying size, often described using the “6 Ps” (purple, pruritic, polygonal, planar, papules and plaques), characterized by the classic Wickham striae

- Typically located on the extremities (Fig. 7) but occasionally presents with generalized involvement and can include the scalp and nails.

- Other anatomical locations that can be affected include the genital mucosa, oesophagus, ocular, urinary, nasal, laryngeal, otic, gastric and anal mucosa.

Association with Systemic Diseases:

OLP is associated with various systemic diseases, including hepatitis C, hypertension, diabetes and thyroid diseases

Strong evidence that HCV is associated with OLP and is possibly involved in its pathogenesis. It would be prudent to ask patients with OLP about risk factors associated with HCV and to request an HCV antibody determination if concerned.

Differential Diagnoses:

- Reticular and erythematous lesions: OLLs and discoid lupus erythematosus

- Atrophic and ulcerative forms: pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigoid and liner immunoglobulin (Ig)-A disease (differentiated by reticulation).

- Plaque form: oral leukoplasia, proliferative verrucous leukoplakia (PVL)

Regardless of their initial diagnosis, these patients with white multifocal lesions should be carefully monitored for early malignant transformation.

Diagnosis:

- Involves assessing the clinical appearance

- Biopsy and pathology study should be performed to confirm diagnosis due to the need for long-term treatment, and the risk of malignant transformation

| Type | Findings |

| Clinical criteria | Presence of bilateral, more or less symmetrical white lesions affecting the buccal mucosa, tongue, lips, and/or gingiva. Presence of white papular lesions and a lace-like network of slightly raised white lines (reticular, annular, or linear pattern) with or without erosions and ulcerations. Sometimes presents as desquamative gingivitis. |

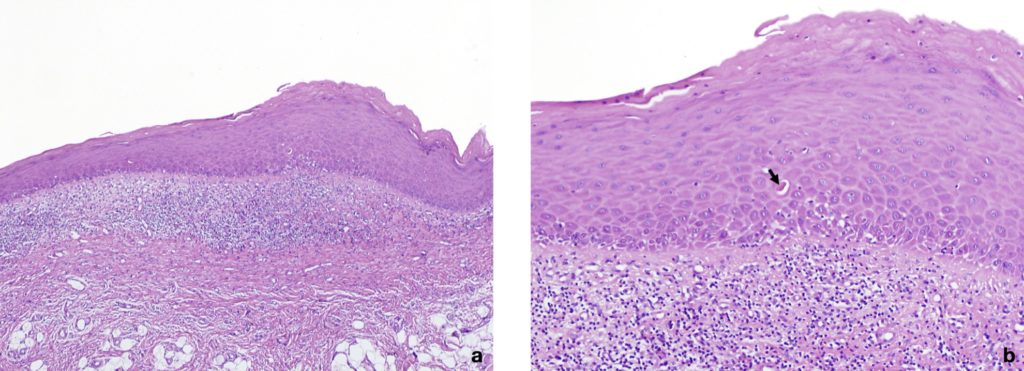

| Histopathological criteria | Presence of a well-defined band-like predominantly lymphocytic infiltrate that is confined to the superficial part of the connective tissue. Signs of vacuolar degeneration of the basal and/or suprabasal cell layers with keratinocyte apoptosis. In the atrophic type, there is epithelial thinning and sometimes ulceration caused by failure of epithelial regeneration as a result of basal cell destruction. A mixed inflammatory infiltrate can be found. |

Table 1: Diagnostic criteria for oral lichen planus (Adapted from Warnakulasuriya et al., 2020)

Management:

- Main objective of OLP treatment is symptom relief – patients with reticular lesions and other asymptomatic lesions need no treatment

- First, the triggers and aggravating factors (sharp or broken teeth, poorly fitted prosthesis, etc.) should be identified and excluded.

- Patients should be advised to cease tobacco and alcohol consumption because they can increase the risk of malignant transformation Patients should also be instructed to maintain good oral hygiene, because reducing dental plaque can have a beneficial effect on gingival lesions

- Sodium-lauryl sulphate (SLS) is a foaming agent added to toothpastes that may exacerbate symptoms and SLS-free toothpastes can be used in preference.

- Symptomatic relief can be obtained by using topical anaesthetic agents such as benzydamine hydrochloride 0.15% (as a spray or mouthwash) or lidocaine gel.

- Topical corticosteroids are the first line agents for treating OLP- A number of preparations are available to be used as mouthwashes: Betamethasone sodium phosphate 500microgram tablets dissolved in 10ml of water up to four times daily, prednisolone 5mg tablets dissolved in 10ml of water or Flixonase 400mcg nasules added to 10ml of water twice daily. Fluticasone propionate spray (50microgram/puff) directed at affected areas 3-4 times daily is useful for isolated lesions.

- For desquamative gingivitis, preparations with corticosteroids in the form of gel applied in individual custom trays are employed, made in soft clear resin or silicone to increase the contact time

Follow-up

- Due to the risk of malignant transformation, regular follow-up should be conducted to assess for relapse

- The frequency of follow-up visits increases proportionally to the disease activity and symptoms

- At a minimum, the recommendation is an annual follow-up and preferably 2 to 4 annual check-ups based on the signs and symptoms of OLP

- If changes in a lesion are observed during the follow-up visits, a biopsy should be performed and follow-up intervals should be shortened

Oral Lichenoid Lesions

Lichenoid lesions are red/white intraoral lesions with a reticular striated appearance similar to OLP but are associated with different known stimuli. The lesions can be divided into oral lichenoid contact lesions (OLCLs), drug-induced OLLs and GVHD-induced OLLs.

Oral Lichenoid Contact Lesions:

- OLCL is used to describe oral lesions that resemble lichen planus, both clinically and histopathologically

- Believed to be caused by a localized hypersensitivity reaction (hypersensitivity mediated by delayed immunity) to a dental restorative material (amalgam, gold, nickel, acrylic resin), or other contact agents (e.g., cinnamon)

- Present as white lesions or mixed red/white lesions, occasionally ulcerated. OLCLs are generally less symmetrical and more often unilateral than OLP and can lack the typical reticular appearance of OLP, more typically presenting in the plaque or atrophic form

- Diagnostic characteristic is the topographical location directly related to the suspected causal agent

» Show more

- The duration of the contact between the causal agent and the oral mucosa appears to be an important factor in the development of OLCLs

- Diagnosis is usually based on the clinical findings, and the disappearance of the lesion after the elimination/replacement of the restorative material or possible causal agent establishes the diagnosis

- Can perform a patch test to identify potential hypersensitivity reactions; however, studies on its usefulness for diagnosing OLCLs have shown conflicting results. Performing a patch test can also be of assistance for determining the alternative restorative material.

- Clinicians should discuss the potential benefits and risks of removing the amalgam restorations with the patients, describing the cyclic nature of the disease, characterized by periods of exacerbation and spontaneous remission, and the unpredictability of the amalgam removal procedure for resolving the lesions

» View less

Drug induced oral lichenoid lesions:

- Caused or associated with exposure to particular drugs and are uncommon, unlike cutaneous OLLs

- There is a long list of systemic drugs associated with the onset of OLLs, which includes non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, anti-hypertensives, oral hypoglycemic agents, antibiotics, antifungals and monoclonal antibodies

- Usually a temporal association between the onset of oral and/or skin lesions and taking certain drugs; however, the drug reaction can occur at any moment, including years after its introduction

» Show more

- Clinical appearance is unclear, especially compared with other lichenoid lesions, although the unilateral location can help the diagnosis

- The diagnosis is confirmed when there is a regression of the lesion after discontinuing or changing the possible causal drug and after reappearance when restarting the treatment with the same drug

- Medications should be discontinued only after consulting the patient’s physician, and this practice is not always feasible in polymedicated patients

» View less

Graft-Versus-Host Disease:

- GVHD is a complication that occurs in bone marrow or hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients

- Systemic condition with a variety of signs and symptoms and affects multiple locations and organs, including the skin, oral cavity, eyes, gastrointestinal tract and liver, as well as other systems such as the lungs, joints and genitourinary tract.

- Oral involvement of GVHD in its acute form is extremely rare; however, the oral cavity is one of the most commonly affected locations in chronic GVHD

- When chronic GVHD affects the oral mucosa, it is clinically characterized by a lichenoid inflammation that frequently involves the tongue and oral mucosa but can affect any location in the oral cavity and can vary from a limited disease with only mild changes to a more extensive and symptomatic disease.

- The clinical changes include papules, white plaques and hyperkeratotic striae that resemble the Wickham striae found in OLP, as well as erythema and pseudomembranous ulcers

- Clinical characteristics by themselves are often sufficient for establishing the diagnosis, provided that they are present in the context of a patient who has undergone allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

References and Further Reading

Khudhur AS, Di Zenzo G, Carrozzo M. Oral lichenoid tissue reactions: diagnosis and classification. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2014;14:169‐184.

Carrozzo M, Porter S, Mercadante V, Fedele S. Oral lichen planus: A disease or a spectrum of tissue reactions? Types, causes, diagnostic algorhythms, prognosis, management strategies. Periodontol 2000. 2019 Jun;80(1):105-125.

Warnakulasuriya S, Kujan O, Aguirre-Urizar JM, Bagan JV, González-Moles MÁ, Kerr AR, et al. Oral potentially malignant disorders: A consensus report from an international seminar on nomenclature and classification, convened by the WHO Collaborating Centre for Oral Cancer. Oral Dis. 2020 (In press)

McCartan BE, Healy CM. The reported prevalence of oral lichen planus: a review and critique. J Oral Pathol Med 2008;37(8):447–53.

González-Moles MA, Warnakulasuriya S, González-Ruiz I, González-Ruiz L, Ayén Á, Lenouvel D, Ruiz-Ávila I, Ramos-García P. Worldwide prevalence of oral lichen planus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Dis 2020 (In press)

Warnakulasuriya S. White, red, and mixed lesions of oral mucosa: A clinicopathologic approach to diagnosis. Periodontol 2000 2019;80(1):89-104.

van der Meij EH, Mast H, van der Waal I. The possible premalignant character of oral lichen planus and oral lichenoid lesions: a prospective five-year follow-up study of 192 patients. Oral Oncol. 2007;43(8):742-8

Fitzpatrick SG, Hirsch SA, Gordon SC. The malignant transformation of oral lichen planus and oral lichenoid lesions: a systematic review. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014 Jan;145(1):45-56.

Aghbari SMH, Abushouk AI, Attia A, Elmaraezy A, Menshawy A, Ahmed MS, Elsaadany BA, Ahmed EM. Malignant transformation of oral lichen planus and oral lichenoid lesions: A meta-analysis of 20095 patient data. Oral Oncol. 2017;68:92-102

González-Moles MÁ, Ruiz-Ávila I, González-Ruiz L, Ayén Á, Gil-Montoya JA, Ramos-García P. Malignant transformation risk of oral lichen planus: A systematic review and comprehensive meta-analysis. Oral Oncol. 2019;96:121-130

González-Moles MÁ, Warnakulasuriya S, González-Ruiz I, González-Ruiz L, Ayén Á, Lenouvel D, et al. Clinical interpretation of findings from a systematic review and a comprehensive meta-analysis on clinicopathological and prognostic characteristics of oral squamous cell carcinomas (OSCC) arising in patients with oral lichen planus (OLP): Author’s reply. Oral Oncol. 2020 (In press).

González-Moles MÁ, Ramos-García P, Warnakulasuriya S. An appraisal of highest quality studies reporting malignant transformation of oral lichen planus based on a systematic review. Oral Dis. 2020 (In press).

Idrees M, Kujan O, Shearston K, Farah CS. Oral lichen planus has a very low malignant transformation rate: A systematic review and meta-analysis using strict diagnostic and inclusion criteria. J Oral Pathol Med. 2020 (in Press).

Speight PM, Khurram SA, Kujan O. Oral potentially malignant disorders: risk of progression to malignancy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2018;125(6):612-627.

Gonzalez-Moles MA, Scully C, Gil-Montoya JA. Oral lichen planus: controversies surrounding malignant transformation. Oral Dis 2008; 14:229–243.

Mignogna MD, Fedele S, Lo Russo L, Mignogna C, de Rosa G, Porter SR. Field cancerization in oral lichen planus. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33(3):383-9

González-Moles MÁ, Warnakulasuriya S, González-Ruiz I, González-Ruiz L, Ayén Á, Lenouvel D, Ruiz-Ávila I, Ramos-García P. Clinicopathological and prognostic characteristics of oral squamous cell carcinomas arising in patients with oral lichen planus: A systematic review and a comprehensive meta-analysis. Oral Oncol. 2020 (In press)

Andreasen JO. Oral lichen planus. 1. A clinical evaluation of 115 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1968;25(1):31–42.

Alrashdan MS, Cirillo N, McCullough M. Oral lichen planus: a literature review and update. Arch Dermatol Res. 2016;308(8):539-51.

Silverman S Jr, Gorsky M, Lozada-Nur F. A prospective follow-up study of 570 patients with oral lichen planus: persistence, remission, and malignant association. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1985;60(1):30-4

Au J, Patel D, Campbell JH. Oral lichen planus. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2013 Feb;25(1):93-100, vii.

De Rossi SS, Ciarrocca K. Oral lichen planus and lichenoid mucositis. Dent Clin North Am 2014;58: 299–313.

Leao JC, Ingafou M, Khan A, Scully C, Porter S. Desquamative gingivitis: retrospective analysis of disease associations of a large cohort. Oral Dis. 2008;14(6):556–60.

Müller S. Oral lichenoid lesions: distinguishing the benign from the deadly. Mod Pathol. 2017 Jan;30(s1):S54-S67.

Scully C, Carrozzo M Oral mucosal disease: lichen planus. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2008; 46:15–21.

Robledo-Sierra J, van der Waal I. How general dentists could manage a patient with oral lichen planus. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2018;23(2):e198-e202

Tziotzios C, Lee JYW, Brier T, Saito R, Hsu CK, Bhargava K, Stefanato CM, Fenton DA, McGrath JA. Lichen planus and lichenoid dermatoses: Clinical overview and molecular basis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(5):789-804.

Parashar P. Oral lichen planus. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2011;44:89–107.

Fox LP, Lightdale CJ, Grossman ME. Lichen planus of the esophagus: what dermatologists need to know. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(1):175-83

Eisen D. The evaluation of cutaneous, genital, scalp, nail, esophageal,and ocular involvement in patients with oral lichen planus.Oral SurgOral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1999;88:431–6

Cassol-Spanemberg J, Rodríguez-de Rivera-Campillo ME, Otero-Rey EM, Estrugo-Devesa A, Jané-Salas E, López-López J. Oral lichen planus and its relationship with systemic diseases. A review of evidence. J Clin Exp Dent. 2018;10(9):e938-e944.

Baccaglini L, Thongprasom K, Carrozzo M, Bigby M. Urban legends series: lichen planus. Oral Dis. 2013;19(2):128-43

Bigby M. The relationship between lichen planus and hepatitis C clarified. Arch Dermatol 2009; 145: 1048–1050.

Kuten-Shorrer M, Menon RS, Lerman MA. Mucocutaneous Diseases. Dent Clin North Am. 2020 Jan;64(1):139-162.

Lopes MA, Feio P, Santos-Silva AR, Vargas PA. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia may initially mimic lichenoid reactions. World J Clin Cases. 2015 Oct 16;3(10):861-3

McParland H, Warnakulasuriya S. Lichenoid morphology could be an early feature of oral proliferative verrucous leukoplakia. J Oral Pathol Med. 2020 (In press)

Gilligan G, Garola F, Piemonte E, Leonardi N, Panico R, Warnakulasuriya S. Lichenoid proliferative leukoplakia, lichenoid lesions with evolution to proliferative leukoplakia or a continuum of the same precancerous condition? A revised hypothesis. J Oral Pathol Med. 2020 (In press)

Van der Meij EH, Van der Waal I. Lack of clinicopathologic correlation in the diagnosis of oral lichen planus based on the presently available diagnostic criteria and suggestions for modifications. J Oral Pathol Med. 2003;32:507‐512.

Eisenberg E. Clinical controversies in oral and maxillofacial surgery: part one. Oral lichen planus: a benign lesion. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2000;58:1278-85.

Al-Hashimi I, Schifter M, Lockhart PB, Wray D, Brennan M, Migliorati CA, et al. Oral lichen planus and oral lichenoid lesions: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2007;103 (suppl):1-12.

Yamanaka Y, Yamashita M, Innocentini LMA, Macedo LD, Chahud F, Ribeiro-Silva A, Roselino AM, Rocha MJA, Motta AC. Direct Immunofluorescence as a Helpful Tool for the Differential Diagnosis of Oral Lichen Planus and Oral Lichenoid Lesions. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40(7):491-497.

Salgado DS, Jeremias F, Capela MV, et al. Plaque control improves the painful symptoms of oral lichen planus gingival lesions. A short-term study. J Oral Pathol Med. 2013;42: 728-732.

Holmstrup P, Schiøtz AW, Westergaard J. Effect of dental plaque control on gingival lichen planus. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol.1990;69:585‐590.

Adamo D, Calabria E, Coppola N, Lo Muzio L, Giuliani M, Bizzoca ME, et al. Psychological profile and unexpected pain in oral lichen planus: a case-control multicenter SIPMO study. Oral Dis. 2021 (In press)

González-García A, Diniz-Freitas M, Gándara-Vila P, Blanco-Carrión A, García-García A, Gándara-Rey J. Triamcinolone acetonide mouth rinses for treatment of erosive oral lichen planus: efficacy and risk of fungal over-infection. Oral Dis. 2006;12(6):559-65.

Lodi G, Pellicano R, Carrozzo M. Hepatitis C virus infection and lichen planus: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Oral Diseases. 2010;16:601–12

Gonzalez-Moles MA, Ruiz-Avila I, Rodriguez-Archilla A, Morales-Garcia P, Mesa-Aguado F, Bascones-Martinez A, Bravo M. Treatment of severe erosive gingival lesions by topical application of clobetasol propionate in custom trays. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;95(6):688-92.

Gonçalves S., Dionne R.A., Moses G., Carrozzo M. Pharmacotherapeutic Approaches in Oral Medicine. In: Farah C., Balasubramaniam R., McCullough M, (eds). Contemporary Oral Medicine. A comprehensive approach to clinical practice. Springer, Switezerland, 2019.

Carbone M, Goss E, Carrozzo M, et al. Systemic and topical corticosteroid treatment of oral lichen planus: a comparative study with long-term follow-up. J Oral Pathol Med. 2003;32:323‐329.

Eisen D. Hydroxychloroquine sulfate (Plaquenil) improves oral lichen planus: An open trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 1993;28:609–12.

Ho JK, Hantash BM. Systematic review of current systemic treatment options for erosive lichen planus. Expert Rev Dermatol 2012;7:269–82.

Wee JS, Shirlaw PJ, Challacombe SJ, Setterfield JF. Efficacy of mycophenolate mofetil in severe mucocutaneous lichen planus: a retrospective review of 10 patients. Br J Dermatol 2012;167:36–43.

Torti DC, Jorizzo JL, McCarty MA. Oral lichen planus: a case series with emphasis on therapy. Arch Dermatol 2007;143:511–5.

Bruch JM, Treister NS. Immune-Mediated and Allergic Conditions. In: Bruch JM, Treister NS, (eds). Clinical Oral Medicine and Pathology. Humana Press, 2009.

Mignogna MD, Fedele S, Lo Russo L. Dysplasia/neoplasia sur-veillance in oral lichen planus patients: a description of clinical criteria adopted at a single centre and their impact on prognosis. Oral Oncol. 2006;42:819-24.

Ismail SB, Kumar SK, Zain RB. Oral lichen planus and lichenoid reactions: etiopathogenesis, diagnosis, management and malignant transformation. J Oral Sci 2007;49:89–106

Epstein JB, Wan LS, Gorsky M, Zhang L. Oral lichen planus: progress in understanding its malignant potential and the implications for clinical management. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;96 (1):32–7.

Elhadad MA, Gaweesh Y. Hawley retainer and lichenoid reaction: a rare case report. BMC Oral Health. 2019 ;19(1):250.

Larsson A, Warfvinge G. Oral lichenoid contact reactions may occasionally transform into malignancy. Eur J Cancer Prevention 2005;14:525-9.

McCartan BE, McCreary CE. Oral lichenoid drug eruptions. Oral Dis 1997;3:58-63.

Den Haute VV, Antoine JL, Lachapelle JM. Histopathological discriminant criteria between lichenoid drug eruption and idiopathic lichen planus: retrospective study on selected samples. Dermatology. 1989;179:10‐13.

Schmidt-Westhausen AM. Oral lichen planus and lichenoid lesions: what’s new? Quintessence Int. 2020;51(2):156-161

Fortuna G, Aria M, Schiavo JH. Drug-induced oral lichenoid reactions: a real clinical entity? A systematic review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;73(12):1523-1537.

Warnakulasuriya S. Clinical features and presentation of oral potentially malignant disorders. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2018 ;125(6):582-590.

Kuten-Shorrer M, Woo SB, Treister NS. Oral graft-versus-host disease. Dent Clin North Am. 2014;58(2):351-68.