This chapter is intended as a general introduction to histopathological diagnosis of selected oral potentially malignant disorders (OPMDs) for physicians, surgeons, and allied health professionals. It is anticipated that the key aspects discussed in this chapter will provide clinical healthcare professionals with insight into the process of histological diagnosis in order to contextualise the role of the pathologist in the multidisciplinary management of OPMDs. It is not intended as a comprehensive text and will discuss the more common histological features of clinical OPMDs, namely oral lichenoid lesions (OLL) and oral epithelial dysplasia. Histological features of other OPMDs are covered elsewhere.

Accurate histological diagnosis is context dependent since there are several overlapping and non-specific microscopic features. Some microscopic features gain relevance in certain clinical contexts which may otherwise be disregarded as incidental. Prior to microscopic evaluation, the pathologist requires:

- Salient patient demographic information;

- The clinical history and appearance of the OPMD;

- Serological findings (if applicable);

- Details of previous biopsies and, perhaps most importantly;

- A clinical differential diagnosis including the degree of clinical suspicion of malignancy transformation.

This highlights the importance for clear and comprehensive clinical information on the pathology request form which accompanies the specimen. Conversely, clinicians should always consider the pathology report in its clinical context; the histological diagnosis should complement, not contradict, the clinical impression. Clear and open communication between clinician and pathologists underpins effective management.

Oral Lichenoid Lesions (OLL)

- Diverse group of oral inflammatory conditions including, but not limited to, oral lichen planus (OLP), lichenoid reaction (LR), lupus erythematosus (LE) and Graft vs. Host disease (GVHD), which are grouped together on their shared histological features.

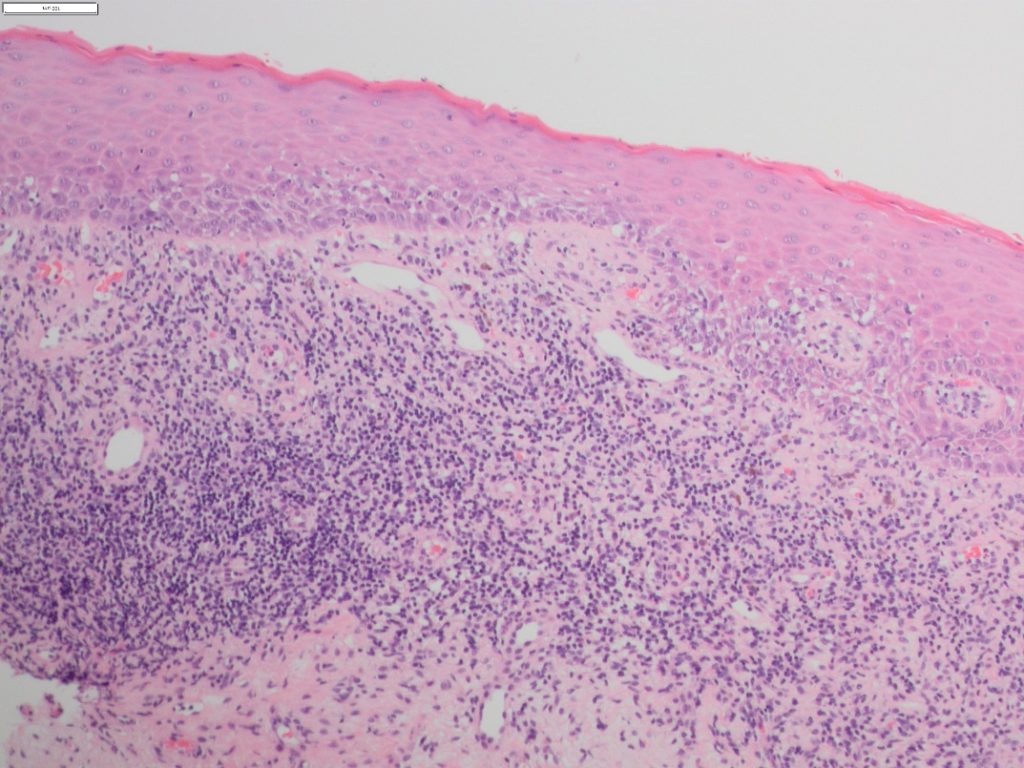

- Individually seen in many different conditions, it is the combination of hyperkeratosis, basal cell degeneration, apoptotic (Civatte) bodies, a sub-epithelial inflammatory infiltrate and lymphocyte exostosis that form the histological foundation for this group (Figure 1).

- Additional findings may include a disturbed rete peg architecture, hyalinization of the basement membrane and pigmentary incontinence.

- It is the alteration in the keratin layer, and not the type nor amount, which is important. The keratin layer may present as either ortho- or para-keratin and extent may vary dependent on the oral cavity site.

- Liquefaction of the basal cells leads to basal squamoid change (apparent extension of the spinous cell layer to the basement membrane).

- The inflammatory infiltrate is usually predominated by lymphocytes with very few plasma cells unless ulceration or Candida are present. Typically, it is dense and band-like with varying degrees of lymphocyte epithelial tropism into the basal cell layers.

- Analysis of the histological differences between OLLs have been shown to be non-significant, however some features are often regarded as favouring a specific OLL.

- Oral lichenoid drug and contact reactions may demonstrate a more diffuse mixed inflammatory infiltrate with a greater frequency of plasma cells. Lymphocyte exocytosis may also be noted extending both further into the suprabasal layers and into the deeper lamina propria with demonstration of perivascular inflammation and lymphoid follicles.

- Rete peg hyperplasia with flame shaped rete processes is associated with LE, occasionally extensive enough to form areas of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. Deep keratin plugging seen in LE skin lesions is not present in oral cavity lesions, however downwards extension of keratin can be present, giving the appearance of low-level keratinisation.

- Oral graft-versus-host disease may show identical histological features to oral lichen planus. The only feature regularly considered to be more suggestive of OGVHD is that the lymphocytic infiltrate is not as intense and, in many cases, resembles more of a ‘burnt out’ appearance.

- Two histological exclusion criteria for all the oral lichenoid lesions are the presence of dysplasia as well as the presence of a verrucous epithelial architecture.

- OLLs as OPMDs have long been a controversial topic. The rationale behind this is that many dysplastic lesions show concurrent lichenoid inflammation and many lichenoid lesions cannot accurately be assessed for the presence of dysplasia, due to the altered basal cell layers and intermingled lymphocyte infiltrate. Therefore, it is essential to always consider the presence of dysplasia in any lichenoid lesion.

- Lichenoid inflammation is also a common finding in oral epithelial dysplasia (OED), in particular those demonstrating verrucous architecture. It has been suggested that this is likely in response to dysplasia within these lesions rather than a true association with an underlying lichenoid lesion.

- In a study by McParland and Warnakulasuriya (2021) of known proliferative verrucous leukoplakia cases, 59% had received an initial clinical diagnosis of OLP and 43% of biopsies had shown lichenoid features.

Although OLLs share many clinicopathological features, it is their differences which are exceedingly important in their diagnosis and only through understanding of the clinical presentation alongside additional findings can correct diagnosis be made. Interpretation of histological assessment should never be made without appreciation for the full clinical context.

Oral Submucous Fibrosis (OSF)

- The characteristic histological feature of oral submucous fibrosis is the presence of dense fibrosis with reduced vascularisation of the lamina propria. Early lesions can be challenging to diagnose before the fibrosis is marked. Special stains, such as Van Gieson, can aid visualization of the parallel arrangement of collagen fibres.

- Hyperkeratosis and epithelial atrophy have also been reported as epithelial changes.

- The inflammatory infiltrate can be variable and may even show a lichenoid inflammatory pattern. Importantly, biopsies should be assessed for the presence of epithelial dysplasia, which is seen in up to 15% of cases.

Oral Epithelial Dysplasia (OED)

The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines OED as ‘a spectrum of architectural and cytological changes associated with an increased risk of progression to squamous cell carcinoma’. Whereas OPMD is ascribed to clinical presentations, OED is histomorphologically defined. Therefore, in addition to the identification of histological features associated with particular disorders, the pathologist will also consider the presence of dysplasia in any OPMD biopsy specimen.

- Architectural changes refer to disordered tissue organisation, while cytological changes indicate individual cell abnormality (Table 1).

- The WHO recognise several features of OED but it should be noted that these features remain subjective since there are no agreed morphometric defining criteria.

- Furthermore, when taken in isolation, each individual feature may also be present in reactive oral mucosal conditions. Nevertheless, these features serve as diagnostic criteria and highlight to the pathologist that the lesion may contain potential for malignant transformation.

- In addition to the features detailed in Table 1, many would also add verrucous surface morphology, subdividing or budding rete processes, spontaneous apoptosis in the absence of intraepithelial inflammatory cells, ortho- or para-keratosis with abrupt lateral demarcation and a subepithelial lymphocytic infiltrate mimicking OLLs.

- Some groups also utilise the term ‘differentiated dysplasia’, namely expansion of the suprabasal compartment by large cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and intercellular oedema. These latter architectural features are frequently mistaken for reactive hyperplastic changes.

| Architectural changes | Cytological changes |

| Irregular stratification | Abnormal variation in nuclear size |

| Loss of polarity of basal cells | Abnormal variation in nuclear shape |

| Bulbous rete ridges | Abnormal variation in cell size |

| Increased number of mitotic figures | Abnormal variation in cell shape |

| Premature keratinization in a single cell | Increased nuclear:cytoplasm ratio |

| Squamous eddies within rete ridges | Atypical mitotic figures |

| Loss of intracellular cohesion | Increased number and size of nucleoli |

| Hyperchromasia |

Table 1. Modified WHO morphologic criteria of OED. Verrucous surface morphology, subdividing rete pegs, spontaneous apoptosis, abruptly demarcated pattern of keratosis and bulky suprabasal proliferation are also increasingly accepted features.

Currently, there is lack of evidence to indicate that any single feature should carry greater significance in predicting malignant transformation. Moreover, there seems to be relatively poor correlation between genetic aberrations and morphologic changes. Therefore, when evaluating dysplasia, rather than applying any points-based algorithmic approach, pathologists undertake a global overview of the epithelial changes, taking into account the intraoral subsite and its clinical presentation.

- There is a positive correlation between the likelihood and time to malignant transformation with increasing degrees of dysplasia. However, published predictive values of malignant transformation have wide confidence intervals due to poor inter-observer reproducibility, methodological heterogeneity, and variable follow-up periods.

- Predictive values may be improved using ploidy and loss of heterozygosity analyses as adjuncts to histological grading, but these are not currently available beyond highly specialised or research centres.

- Since OED is a spectrum of morphological changes, histological grading of dysplasia is essential to inform subsequent management of any given OPMD.

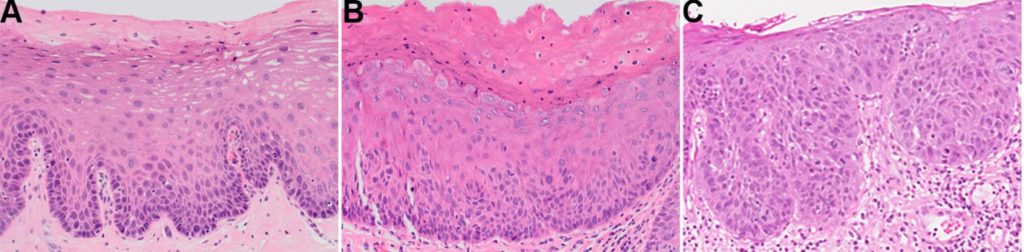

- Most centres utilise a three-tier grading system for OED of mild, moderate and severe dysplasia (Figure 2) with carcinoma in situ being synonymous with the last.

- This system is partly guided by the epithelial thickness in thirds affected by architectural and cytological change. However, it should be emphasised that mild, moderate, and severe dysplasia do not necessarily equate to changes limited to the basal, middle, and superficial thirds of the epithelium, respectively. For example, it is possible for the dysplasia to be graded as severe despite changes being limited to the basal third, highlighting how grading is a global assessment of morphologic changes.

- Nevertheless, since the cut-offs between each grade are poorly defined, suboptimal interobserver reproducibility is compounded.

- To overcome this, some authorities advocate a binary grading system (high- versus low-grade) and suggest cut-off criteria between the grades.

- In future, reproducibility may be enhanced by incorporating artificial intelligence platforms.

- Ultimately, the goal of any grading system is not reproducibility, but to inform clinical management within a multidisciplinary context.

- The pathologist’s intent in assigning a grade should be clear to the clinician regardless of the system used, further emphasising the need for good multidisciplinary working relationships for effective management of OPMDs.

Hyperkeratotic lesions frequently contain concurrent Candida spp. infections. The reactive (and therefore reversible) squamous epithelial response to fungal hyphae results in phenotypic changes which are indistinguishable from dysplasia. In such circumstances, it would be prudent to consider definitive histological grading of OED following elimination of candida infection, clinical re-assessment and/or re-biopsy.

Human Papillomavirus - Associated Oral Epithelial Dysplasia (HPV OED)

- A subset of OED is known to be associated with high-risk types of human papillomavirus (HPV), mainly HPV-16.

- The virus induces somewhat distinct histomorphological epithelial changes, namely karryorhexis, isolated suprabasal apoptotic keratinocytes, abortive mitotic forms (mitosoid bodies) and variable koilocyte-like cells within the superficial strata.

- These morphological features on their own are insufficiently specific to confirm a virus-driven aetiology necessitating testing for transcriptionally active high-risk HPV.

- The presence of biologically significant high-risk HPV may be demonstrated by strong and diffuse block positivity for p16 (often with sharp lateral demarcation) followed by in situ hybridisation for viral DNA or RNA.

- HPV testing by consensus PCR alone, in the absence of viral cytopathic changes, is insufficiently specific for HPV OED.

- Anecdotal reports of progression to carcinoma in HPV OED have been reported in small case series, but the overall malignant transformation rates currently remain unknown.

- Since there is no accepted grading system, HPV OED should for the present be graded and clinically managed according to conventional criteria.

References and Further Reading

Alberdi-Navarro, J., et al., Histopathological characterization of the oral lichenoid disease subtypes and the relation with the clinical data. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal, 2017. 22(3): p. e307-e313.

Arsenic, R. and M.O. Kurrer, Differentiated dysplasia is a frequent precursor or associated lesion in invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity and pharynx. Virchows Arch, 2013. 462(6): p. 609-17.

Cai, X., et al., Oral submucous fibrosis: A clinicopathological study of 674 cases in China. J Oral Pathol Med, 2019. 48(4): p. 321-325.

Cheng, Y.S., et al., Diagnosis of oral lichen planus: a position paper of the American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol, 2016. 122(3): p.

Davidova, L.A., et al., Lichenoid Characteristics in Premalignant Verrucous Lesions and Verrucous Carcinoma of the Oral Cavity. Head Neck Pathol, 2019. 13(4): p. 573-579.

de la Cour, C.D., et al., Human papillomavirus prevalence in oral potentially malignant disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Dis, 2021. 27(3): p. 431-438.

Fitzpatrick, S.G., et al., Histologic lichenoid features in oral dysplasia and squamous cell. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2014 Apr;117(4):511-20.

Fonseca-Silva, T., et al., Association between histopathological features of dysplasia in oral leukoplakia and loss of heterozygosity. Histopathology, 2016. 68(3): p. 456-60.

Iocca, O., et al., Potentially malignant disorders of the oral cavity and oral dysplasia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of malignant transformation rate by subtype. Head Neck, 2020. 42(3): p. 539-555.

Lu, R. and G. Zhou, Oral lichenoid lesions: Is it a single disease or a group of diseases? Oral Oncol, 2021. 117: p. 105188.

Khanal, S., et al., Histologic variation in high grade oral epithelial dysplasia when associated with high-risk human papillomavirus. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol, 2017. 123(5): p. 566-585.

Kujan, O., et al., Evaluation of a new binary system of grading oral epithelial dysplasia for prediction of malignant transformation. Oral Oncol, 2006. 42(10): p. 987-93.

Lerman, M.A., et al., HPV-16 in a distinct subset of oral epithelial dysplasia. Mod Pathol, 2017. 30(12): p. 1646-1654.

McCord, C., et al., Association of high-risk human papillomavirus infection with oral epithelial dysplasia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol, 2013. 115(4): p. 541-9.

McParland, H. and S. Warnakulasuriya, Lichenoid morphology could be an early feature of oral proliferative verrucous leukoplakia. J Oral Pathol Med, 2021. 50(2): p. 229-235.

Mahmood, H., et al., Use of artificial intelligence in diagnosis of head and neck precancerous and cancerous lesions: A systematic review. Oral Oncol, 2020. 110: p. 104885.

Mehanna, H.M., et al., Treatment and follow-up of oral dysplasia – a systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Neck, 2009. 31(12): p. 1600-9.

Muller, S., Oral lichenoid lesions: distinguishing the benign from the deadly. Mod Pathol. 2017 Jan;30(s1):S54-S67.

Nankivell, P., et al., The binary oral dysplasia grading system: validity testing and suggested improvement. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol, 2013. 115(1): p. 87-94.

Nishat, R. and H. Kumar, Collagen fibers in oral submucous fibrosis – A polarizing microscopy study using two special stains. Indian J Pathol Microbiol, 2019. 62(4): p. 537-543.

Odell, E., et al., Oral epithelial dysplasia: recognition, grading and clinical significance. Oral Dis, 2021.

Odell, E.W., et al., Precursor Lesions for Squamous Carcinoma in the Upper Aerodigestive Tract, in Gnepp’s Diagnostic Surgical Pathology of the Head and Neck, D. Gnepp and B.J. A., Editors. 2020, Elsevier.

Odell, E.W., Aneuploidy and loss of heterozygosity as risk markers for malignant transformation in oral mucosa. Oral Dis. 2021 Nov;27(8):1993-2007.

Reibel, J., et al., Oral potentially malignant disorders and oral epithelial dysplasia, in WHO Classification of Head and Neck Tumours 4th edition, World Health Organisation Classification of Tumours, A.K. El Naggar, et al., Editors. 2017, IARC: Lyon, France.

Wils, L.J., et al., Incorporation of differentiated dysplasia improves prediction of oral leukoplakia at increased risk of malignant progression. Mod Pathol, 2020. 33(6): p. 1033-1040.

Woo, S.B., Oral Epithelial Dysplasia and Premalignancy. Head Neck Pathol, 2019. 13(3): p. 423-439.