Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) is a chronic inflammatory condition affecting skin and oral mucosa. DLE is the most common variant of chronic cutaneous lupus comprising 80% of cases. The pathophysiology of the disease is complex and involves multiple factors including genetics, environmental factors and the innate and adaptive immune system. The most common environmental triggers for DLE include UV irradiation, drugs, radiotherapy and smoking.

Epidemiology

- Prevalence of DLE ranges from 9-70 cases per 100,000 population.

- DLE incidence is 3-5 times higher in Asian and Black ethnic groups compared to White ethnic groups

- Predominantly affects women with a female to male ratio of 3:1.

- Most often develops in persons aged 20-40 years.

- Oral lesions are present in 20% of DLE patients.

- Occurrence of oral lesions in DLE patients without cutaneous involvement is rare and reported in 10% of cases

Clinical presentation

- Most common presentation of chronic cutaneous lupus is DLE which may occur as localized type (80%) with lesions presenting on the face, ears and scalp.

- Disseminated DLE (20% of cases) presents with lesions above and below the neck and is associated with an increased risk of progression to systemic lupus erythematosus

Cutaneous Lesions:

- DLE cutaneous lesions present on sun exposed areas of the face and neck with annular erythema and follicular hyperkeratosis. A characteristic plaque over the malar area of the face and bridge of the nose in a butterfly pattern had been described.

- The skin lesions may be accompanied by an itching or burning sensation.

- As the skin lesions progress, central atrophy, scarring, telangiectasia and hypopigmentation occur. Irreversible scarring alopecia on the scalp also occurs

Oral Lesions:

- Oral lesions occur in approximately 20% of cases and typically affects the lips, hard palate and buccal mucosa

- Oral DLE lesions are characterized by the presence of central erythema or ulceration surrounded by hyperkeratotic papules or radiating striae, and peripheral telangiectasia (Figures 1 and 2). The “honeycomb” appearance occurs in long-standing lesions.

- Mucosal lesions may occur without involvement of the skin or prior to the development of skin lesions. Lip lesions may spread to involve the adjacent skin, obscuring the vermilion border.

- Desquamative gingivitis affecting lower and/or upper gingiva may also be present

- With healing, erosive lesions may leave post-inflammatory pigmentation.

- The most common symptoms of DLE include a burning sensation, photosensitivity, dryness, tenderness and pain, but lesions can be asymptomatic

- DLE patients have increased risk of cancer, including non-melanoma skin cancer and oral cancer, compared to the general population

- The World Health Organization categorized DLE as an oral potentially malignant disorder though malignant transformation is rare

- More commonly, malignant transformation occurs in DLE lesions localized to the vermilion border of the lip, with the lower lip more often affected.

- Long-term ultraviolet light exposure, chronic scarring, HPV infection and long-term immunosuppressive therapy may be predisposing factors for the development of SCC. The mean duration from the onset of DLE to the development of lip cancer is shorter compared to cancers originating from DLE lesions at other sites (10-13 years vs. 19-26 years).

- DLE-related cancers are more aggressive and have higher metastatic potential (10-25%), recurrence rates (27-29%) and mortality (19.4%) compared to non-DLE related cancers (20%, 0.5-6% and 1%, respectively)

Differential diagnoses

The differential diagnosis of DLE oral lesions includes oral lichen planus (OLP), lichenoid reactions, oral leukoplakia and actinic cheilitis (when the lower lip is affected).

In the case of OLP, lesions are more widespread and more symmetrically distributed, and the reticular pattern is more pronounced unlike in DLE oral lesions.

Lichenoid reactions present as white striae in sites directly in contact with amalgam restoration. Following removal of the restoration, the lesion improves or resolves.

Oral leukoplakia does not exhibit a radial pattern of hyperkeratotic striae and does not present with central atrophy.

Actinic cheilitis usually involves the lower lip presenting with scabbing and without striae formation.

Diagnosis

- Diagnosis of DLE can be challenging in light of the similarities with oral lichen planus in histopathology.

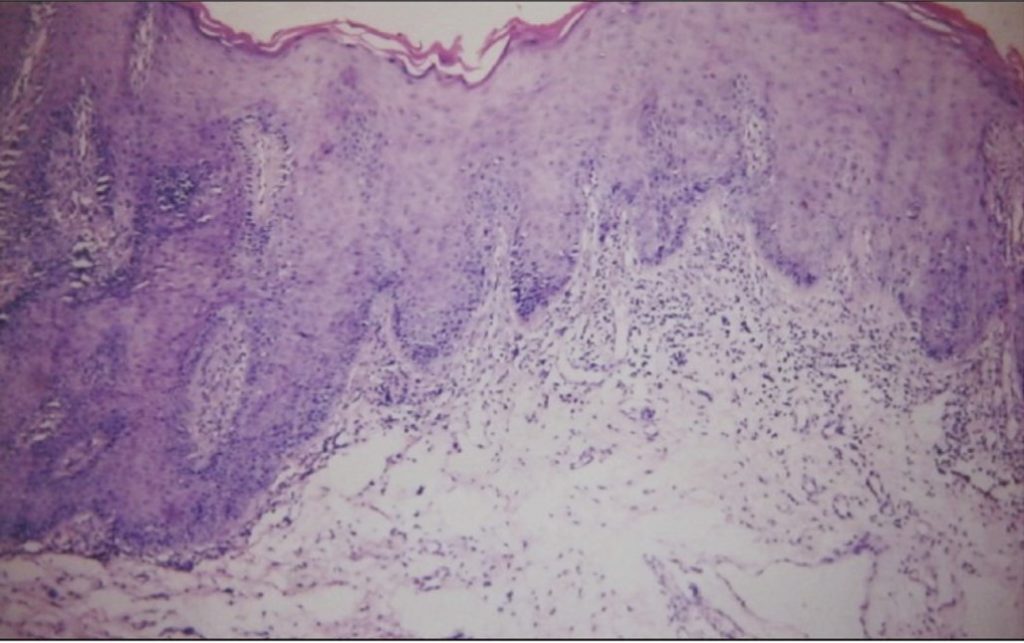

- Histological findings of oral DLE include hyperkeratosis with keratotic plugs, atrophy of the rete ridges, hydropic degeneration of the basal cell layer, interface mucositis with superficial or deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, oedema in the lamina propria and PAS positive thickening of blood vessel walls (Figure 3).

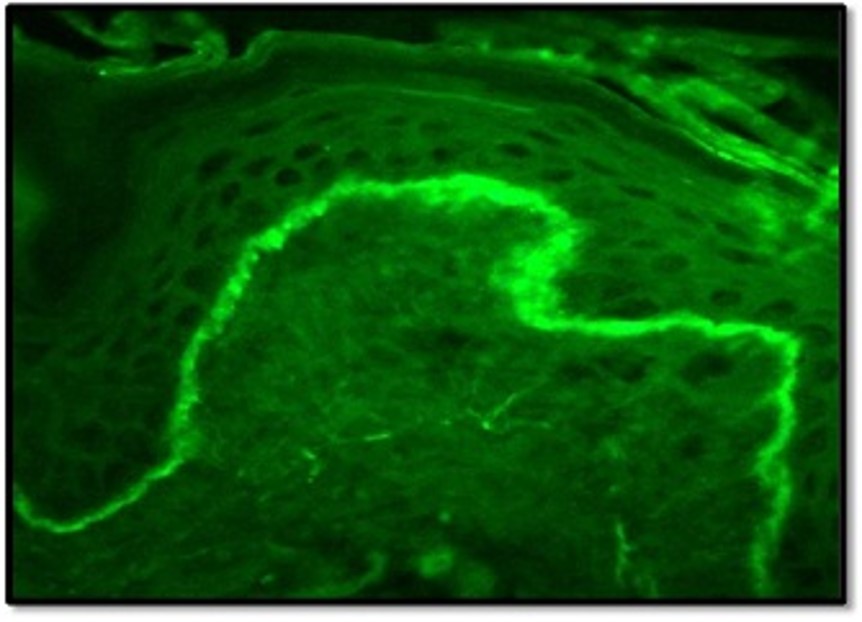

- Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) may be helpful for further analysis. DLE lesions demonstrate linear or granular deposition of IgM, IgG and complement 3 (C3) at the basement membrane zone- the ‘lupus band’ (Figure 4).

- In contrast to DLE, fibrinogen deposits can be found in 90-100% of the OLP patients along the basement membrane. Due to the marked difference in DIF findings between DLE and oral lichen planus, many authors believe DIF should be part of the diagnostic standard when it is suspected.

- Serological and haematological abnormalities may be detected in DLE patients. In some cases, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate may be elevated. Approximately 20% of patients have positive antinuclear antibody (ANA) and up to 20% have SS-A autoantibodies. Anti-Sm autoantibodies, usually seen in systemic lupus erythematosus, may occur in 5-20% of DLE patients.

Management

- Patients should be made aware of the possibility of progressing to systemic disease. The risk of progression from DLE to SLE is 16.7% within 3 years of diagnosis and 17% within 8 years of diagnosis. Preventive measures include avoidance of UV exposure and smoking cessation.

- Some evidence on the use of topical fluocinonide cream, systemic hydroxychloroquine and acitretin in patients with DLE affecting the skin, the evidence for oral DLE management is sparse.

Localised Oral Lesions:

- Topical treatment is first-line. Topical corticosteroids (triamcinolone acetonide, betamethasone valerate, clobetasol diproprionate, hydrocortisone, fluocinolone acetonide) are the mainstay of therapy.

- Calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus, pimecrolimus) may also be used.

- Intralesional injection of corticosteroids (triamcinolone acetonide) is useful for individual lesions.

Recalcitrant lesions or widespread disease

- Systemic therapy is often needed e.g Antimalarials (hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine and quinacrine) alone or in combination with systemic corticosteroids are used as first-line systemic drugs.

- In more severe cases, immunomodulators (dapsone, thalidomide, lenalidomide) and/or oral retinoids (acitretin, isotretinoin, alitretinoin) and/or immunosuppressives (methotrexate, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, mycophenolate sodium, cyclosporine) can be used.

- Biologic agents (rituximab, belimumab) are used in the most severe cases.

Patients with DLE should be monitored at regular intervals. Response to therapy differs for each patient, varying from a few weeks to months. Each patient should be managed on a case-by-case basis for the purposes of symptom control and surveillance for potential malignant transformation.

References and further reading

Warnakulasurya S. Clinical features and presentation of oral potentially malignant disorders. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2018;125:582–90.

Stannard JN, Kahlenberg JN. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: updates on pathogenesis and associations with systemic lupus. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2016;28(5): 453–9.

Grönhagen CM, Fored CM, Granath F, Nyberg F. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus and the association with systemic lupus erythematosus: a population-based cohort of 1088 patients in Sweden. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164(6):1335-41.

Blake SC, Daniel BS. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: A review of the literature. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019;5(5):320-9.

Szczęch J, Samotij D, Werth DP, Reich A. Trigger factors of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: a review of current literature. Lupus. 2017;26(8):791-807.

Izmirly PM, Buyon JP, Belmont HM, Sahl S, Wan I, Salmon JE et al. Population-based prevalence and incidence estimates of primary discoid lupus erythematosus from the Manhattan Lupus Surveillance Program. Lupus Sci Med. 2019;6(1):e000344.

Jarukitsopa S, Hoganson DDD, Crowson CS, Sokumbi O, Davis MD, Michet CJ et al. Epidemiology of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and Cutaneous Lupus in a Predominantly White Population in the United States. Arthritis Care Res. 2015; 67(6): 817–28.

Drenkard C, Parker S, Aspey LD, Gordon C, Helmick CG, Bao G, Sam Lim S. Racial disparities in the incidence of primary chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus in the southeastern US: the Georgia lupus registry. Arthritis Care Res. 2019; 71:95–103.

Nico MMS, Apparecida M, Vileila C, Rivitti EA, Lourenco SV. Oral lesions in lupus erythematosus: correlation with cutaneous lesions. Eur J Dermatol 2008;18(4):376-81.

Menzies S, O’Shea F, Galvin S, Wynne B. Oral manifestations of lupus. Ir J Med Sci. 2018; 187:91–3.

Ranginwala AM, Chalishazar MM, Panja P, Buddhdev KP, Kale HM. Oral discoid lupus erythematosus: A study of twenty-one cases. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2012;16(3): 368–73.

Lallas A, Apalla Z, Lefaki I, et al. Dermoscopy of discoid lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol 2013;168: 284–8.

McDaniel B, Sukumaran S,Tanner LS. Discoid Lupus Erythematosus. NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-.

Shafer WG, Hine MK, Levy BM. A textbook of oral pathology. 7th ed. Philadelphia: W B Saunders;1999. p. 8992.

Kranti K, Seshan H, Juliet J. Discoid lupus erythematosus involving gingiva. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2012;16(1): 126–8.

Grönhagen CM, Fored CM, Granath F, Nyberg F. Increased risk of cancer among 3663 patients with cutaneous lupus erythematosus: A Swedish nationwide cohort study. Br J Dermatol 2012; 166: 1053–1059.

de Berker D, Dissaneyeka M, Burge S. The sequelae of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Lupus 1992;1:181-6.

Warnakulasuriya S, Johnson NW, van der Waal I. Nomenclature and classification of potentially malignant disorders of the oral mucosa. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36:575-580.

Arvanitidou IE, Nikitakis NG, Georgaki M, Papadogeorgakis N, Tzioufas A, Sklavounou A. Multiple primary squamous cell carcinomas of the lower lip and tongue arising in discoid lupus erythematosus: a case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2018;125:e22-e30.

Fernandes MS, Girisha BS, Viswanathan N, Sripathi H and Noronha TM. Discoid lupus erythematosus with squamous cell carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature in Indian patients. Lupus. 2015; 24: 1562–6.

Sherman RN, Lee CW, Flynn KJ. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in black patients with chronic discoid lupus erythematosus. Int J Dermatol 1993; 32: 677–679.

Liu W, Shen ZY, Wang LJ, et al. Malignant potential of oral and labial chronic discoid lupus erythematosus: A clinicopathological study of 87 cases. Histopathology 2011; 59: 292–298.

Tao J, Zhang X, Guo N, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma complicating discoid lupus erythematosus in Chinese patients: Review of the literature, 1964–2010. J Am Dermatol 2012; 66: 695–696.

Makita E, Akasaka E, Sakuraba Y, Korekawa A, Aizu T, Kaneko T et al. Squamous cell carcinoma on the lip arising from discoid lupus erythematosus: a case report and review of Japanese patients. Eur J Dermatol. 2016;26(4):395-6.

Naik V, Prakash S. Oral Discoid Lupus Erythematosus: A Case Effectively Managed and Differentiated with other Overlapping Diseases. Indian J Dent Adv 2018;9(4): 221-5.

Del Barrio‐Díaz P, Reyes‐Vivanco C, Cifuentes‐Mutinelli M, Manríquez J, Vera‐Kellet C. Association between oral lesions and disease activity in lupus erythematosus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(2):349-356.

Martins da Costa Marques ER, Silva R, Hsieh R. Oral Mucosal Manifestation of Lupus Erythematosus: A Short Review. DOBCR. doi: 10.31487/j.DOBCR.2020.02.09

Bhushan R, Agarwal S, Chander R, Agarwal K. Direct Immunofluorescence Study in Discoid Lupus Erythematosus. World Journal of Pathology 2017; 9:56-60.

Biazar C. Sigges J. Patsinakidis N. Ruland V. Amler S. Bonsmann G. Kuhn A. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: first multicenter database analysis of 1002 patients from the European Society of Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus (EUSCLE).Autoimmun Rev. 2013; 12(3):444-454.

Wieczorek I.T., Propert K.J., Okawa J, Werth V.P. Systemic symptoms in the progression of cutaneous to systemic lupus erythematosus. JAMA Dermatol. 2014; 150(3):291-6.

Jessop S, Whitelaw DA, Grainge MJ, Jayasekera P. Drugs for discoid lupus erythematosus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;5(5):CD002954.

Okon LG, Werth VP. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: diagnosis and treatment. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2013;27: 391-404.